Victorian Police Strike & Riots | 1923 |

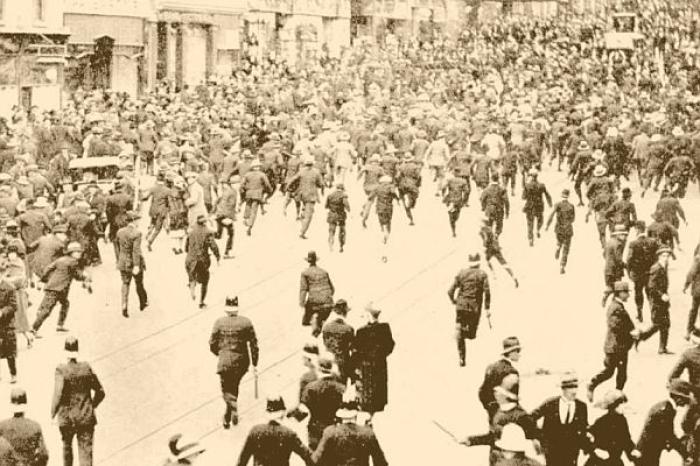

The 1923 Victorian Police Strike is one of Victorian history's most remarkable and strangest strikes because it provoked the worst public riots ever seen in Melbourne, let alone Australia.

What makes the riots even more extraordinary is not only the senselessness of the violence, but also that it was reported that rioters included members of the police force, with some reports of dissenting officers attacking one another in the streets, at times using firearms.

Why Can't We All Get Along?

What had caused the police to go on strike were tense relations between officers and the government that had been lurking in the background for quite some time. Relations had long been strained for more than 20 years after parliament had abolished police pensions.

Tensions within the police force were already high what with police staff having very little respect for the Chief Commissioner, Alexander Nicholson. True the old adage that it's 'who you know, and not what you know,' it was widely felt by officer that Nicholson had only been appointed the role because of his friendship with the chief secretary of the Victorian Parliament.

The dislike of Chief Commissioner Nicholson, who many believed lacked any true regional policing experience, was only deepened when Victoria's police found that 'special supervisors' - essentially spies - had been placed within their ranks by Nicholson to monitor the police force's performance.

This was following the further indignity of having had their pay cut back, along with the terrible working conditions they had suffered where in some case horses were actually treated much better than the men who served as police officers.

That the police felt compelled to go on strike is hardly surprising, given the rather hostile climate they were facing within their own occupation. Whether they'd have gone ahead with their strike, had they known what was to follow, is another matter entirely.

While there must have been at least some anticipation that there'd be some public unrest in the absence of a fully manned police force, they couldn't possibly have been prepared for the chaos that would ensue.

We Shall Not Be Blu-u-u-ue..

As with many strikes held today, the timing of the Police strike was planned at a time when it would have no doubt been thought that both the Victorian Parliament and the Chief Commissioner would bow to their not unreasonable demands.

Choosing their opportune moment, the Police strike began on October 31st in 1923, the eve of Melbourne's Spring Racing Carnival, when a squad of 24 constables at the Russell Street Police Headquarters refused to perform their duties, citing their main concerns as the recent and continued use of spies within their ranks, and the fact that the Government had persistently deferred any promises of re-introducing a pension program.

That there was enough dissent with the Victorian Police Force that they'd strike can't have been a surprise to their superiors. The strike was led by Constable William Thomas Brooks, a member of the licensing squad, who only two years earlier had circulated a petition that called for better conditions among his fellow officers. Signed by almost 700 men, it was undeniable that there had to be change. With the strike including an equally impressive number of police staff, most of them constables who were returned servicemen, it was only Detectives and senior officers who didn't participate.

While the strike wasn't an overall initiative of the Police Association, the organisation did in fact negotiate with the Premier, Harry Lawson, on behalf of the striking policemen. The Victorian Trades Hall Council, as surprised by the strike as the Government and public, also offered to help negotiations. Their assistance was rejected by the Government, however, revealing a stubborn tenacity that they'd maintain to the bitter end.

Within 24 hours of the strike the Victorian Premier issued a demand that officers return to work and promised that there'd be no victimisation of participating officers. With no promise of meeting any of the strikers' demands, however, the strike continued. After 48 hours of the strike's continuation, the Premier once again demanded their return to work, but this time he pointedly made no guarantees that officers wouldn't be penalised for their actions.

There's Panic On The Streets Of Melbourne

Although the strike was held state-wide it was Melbourne that saw the most uncharacteristic displays of unrest from the public, especially when it became clear that the strike was far from a knee-jerk reaction and was likely to last several days.

With an incredibly sparse police presence on the streets, there had already been signs of people taking advantage of the absence of the boys in blue, but it was the weekend of the 3rd and 4th on November when things became much worse, particularly on the Friday and Saturday nights when there were stunning displays of unruly behaviour.

The city of Melbourne saw riots and looting occur, the likes of which had never been witnessed with a great deal of the crimes being ones of opportunity where store windows were smashed and merchandise was stolen. Theatre-goers were also reported to have been terrorised by the wild mobs.

On both nights the rioting began at Flinders Street Station (because who brings their car to a riot, seriously?) and the unrest was carried on further along Elizabeth and Swanston Streets. The disturbances were so chaotic that three deaths were caused, and Constables placed on point duty were jeered at and harassed by mobs until they were forced to retreat to the Town Hall, where the waiting mob taunted them to come out.

Rioting was so severe that trams were even overturned, and according to a book about the riots by Gavin Brown and Robert Haldane, Days of Violence (published by Hybrid Publishers), there were even cases of dissenting Police Officers attacking one another, at times using firearms in the streets.

While much of the chaos and theft was attributed by many of Australia's newspapers to Melbourne's criminal element, with Squizzy Taylor bearing a lot of that brunt, court records would later show that most offenders who were apprehended during the riots were in fact young men and boys who had no previous histories of crime.

During the chaotic weekend, the Premier, Harry Lawson, issued a request to the Federal Government asking for troops to be called in and put an end to the trouble, but the request was denied. Lacking Federal assistance, it was left to Sir Harry Chauvel, a general officer of the First Australian Imperial Force, and other army chiefs to appoint guards from local defence establishments to help retain order.

Over the course of the weekend volunteering 'special constables' were also sworn in to restore peace under the direction of Sir John Monash at the Melbourne Town Hall. Many of the men, who were identified by special armbands, were returned servicemen, much like the police officers they were replacing. Issued with only an armband, an instruction booklet and a baton, the volunteers took to the streets when the Police Force would not.

Ironically, many of the returned servicemen who volunteered had been in quite the stoush themselves with the police, some years earlier. Unhappy with their treatment upon returning from World War I, it hadn't been that long ago when these men had spent a good few days rioting themselves, following the Peace Day rally of July 19 in 1919.

During these earlier riots, many of those who were now volunteer constables had forced their way into the Premier's office, beaming him on the head with an inkstand. Bygones were clearly bygones, as the same target of their unrest had now given these men full powers to use the batons that they had been issued, and it's believed that as many of the injuries caused during riots might have been attributed to the overzealous volunteers.

Many of these same men, once at the receiving end of a baton, went on to be official Police Officers once the rioting that the strike had inspired passed. Given the seriousness of the riots that ensues, the Premier's threat that striking officers would not be safe from repercussions proved very true.

Sadly, the benefits that the strike had intended to achieve were enjoyed only by those who had stepped in as volunteers during the chaos. Following the strike it eventuated that more than 600 of the striking policemen were discharged, stripping back almost a third of the Victorian Police Force, never to be re-employed as active members again.

After the findings of the Monash Royal Commission into the Victoria Police strike were released, the government subsequently increased pay and conditions for police, including a bill to establish a police pension scheme before the end of 1923.

1923 | Victorian Police Strike & Riots

❊ Web Links ❊

➼ Victorian Police Strike & Riots | 1923

➼ www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1923_Victorian_Police_strike

➼ www.museumsvictoria.com.au/marvellous/contrasts/protest.asp

➼ www.policejournalsa.org.au/9812/17a.html

➼ www.hybridpublishers.com.au/titles/11.html

❊ Also See... ❊

➼ Victoria Police

Disclaimer: Check with the venue (web links) before making plans, travelling or buying tickets.

Accessibility: Contact the venue for accessibility information.

Update Page